Did Hitler Register All The Guns In His Country

Source: NY Review of Books (2/5/18)

Who Killed More: Hitler, Stalin, or Mao?

By Ian Johnson

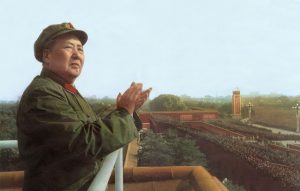

Chairman Mao attending a military review in Beijing, China, 1967 (Photo by Apic/Getty Images)

In these pages nearly seven years ago, Timothy Snyder asked the provocative question: Who killed more, Hitler or Stalin? As useful as that exercise in moral rigor was, some recall the question itself might have been slightly off. Instead, it should accept included a third tyrant of the twentieth century, Chairman Mao. And not just that, but that Mao should take been the hands-downwardly winner, with his ledger easily trumping the European dictators'.

While these questions tin can devolve into morbid pedantry, they enhance moral questions that deserve a fresh look, especially as these months mark the sixtieth anniversary of the launch of Mao'southward nigh infamous experiment in social engineering, the Great Bound Forward. It was this entrada that caused the deaths of tens of millions and catapulted Mao Zedong into the big league of twentieth-century murders.

But Mao's mistakes are more than a chance to reflect on the past. They are too at present part of a cardinal debate in Xi Jinping's China, where the Communist Party is renewing a long-standing boxing to protect its legitimacy past limiting discussions of Mao.

The firsthand catalyst for the Great Bound Forward took identify in late 1957 when Mao visited Moscow for the grand celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the October Revolution (some other interesting contrast to recent months, with discussion of its centenary stifled in Moscow and largely ignored in Beijing).

The Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, had already annoyed Mao by criticizing Stalin, whom Mao regarded as one of the great figures of Communist history. If even Stalin could be purged, Mao could exist challenged, also. In addition, the Soviet Spousal relationship had merely launched the globe's showtime satellite, Sputnik, which Mao felt overshadowed his accomplishments. He returned to Beijing eager to assert Cathay'south position as the earth'due south leading Communist nation. This, along with his general impatience, spurred a series of increasingly reckless decisions that led to the worst famine in history.

The showtime signs of Mao's designs came on Jan i, 1958, when the Communist Party'south mouthpiece,People'due south Daily, published an article calling for "going all out" and "aiming higher"—code phrases for putting bated patient economical development in favor of radical policies aimed at rapid growth.

Mao drove habitation his plans in a series of meetings over the next months, including a crucial one—from Jan 11 to xx in the southern Chinese urban center of Nanning—that changed the Communist Political party's political culture. Until that moment, Mao had been get-go among equals, merely moderates had oftentimes been able to rein him in. Then, in several extraordinary outbursts, he accused any leader who opposed "rash advance" of being counter-revolutionary. As became the pattern of his reign, no ane successfully stood up to him.

Having silenced political party opposition, Mao pushed for the creation of communes—effectively nationalizing farmers' property. People were to consume in canteens and share farm machinery, livestock, and product, with food allocated by the state. Local party leaders were ordered to obey fanciful ideas for increasing crop yields, such as planting crops closer together. The thought was to create China'southward own Sputnik—harvests astronomically greater than any in human history.

A rudimentary smelting furnace, part of Mao'southward Great Leap Forward program, in Beijing, 1958. Jacquet-Francillon/AFP/Getty Images

This might have resulted in no more harm than local officials' falsifying statistics to meet quotas, except that the land relied on these numbers to calculate taxes on farmers. To come across their taxes, farmers were forced to transport any grain they had to the state as if they were producing these insanely high yields. Ominously, officials also confiscated seed grain to meet their targets. So, while storehouses bulged with grain, farmers had nothing to swallow and nothing to plant the next leap.

Compounding this crunch were equally deluded plans to bolster steel production through the creation of "backyard furnaces"—small coal- or wood-fired kilns that were somehow supposed to create steel out of iron ore. Unable to produce existent steel, local party officials ordered farmers to melt down their agricultural implements to satisfy Mao's national targets. The result was that farmers had no grain, no seeds, and no tools. Dearth set in.

When, in 1959, Mao was challenged virtually these events at a party conference, he purged his enemies. Enveloped by an atmosphere of terror, officials returned to China'due south provinces to double down on Mao's policies. Tens of millions died.

No independent historian doubts that tens of millions died during the Neat Leap Forward, but the exact numbers, and how one reconciles them, accept remained matters of argue. The overall trend, though, has been to raise the effigy, despite pushback from Communist Political party revisionists and a few Western sympathizers.

On the Chinese side, this involves a cottage industry of Mao apologists willing to do whatever information technology takes to go on the Mao name sacred: historians working at Chinese institutions who argue that the numbers have been inflated past bad statistical work. Their about prominent spokesperson is Sun Jingxian, a mathematician at Shandong University and Jiangsu Normal University. He attributes changes in China'south population during this period as due to faulty statistics, changes in how households were registered, and a series of other obfuscatory factors. His conclusion: famine killed simply iii.66 one thousand thousand people. This contradicts almost every other serious attempt at accounting for the effects of Mao's changes.

The first reliable scholarly estimates derived from the pioneering work of the demographer Judith Banister, who in 1987 used Chinese demographic statistics to come up with the remarkably durable guess of thirty one thousand thousand, and the journalist Jasper Becker, who in his 1996 piece of workHungry Ghosts gave these numbers a man dimension and offered a clear, historical analysis of the events. At the most bones level, the early on works took the net decline in China'south population during this menstruum and added to that the decline in the birth rate—a classic effect of famine. Later scholars refined this methodology by looking at local histories compiled by authorities offices that gave very detailed accounts of famine conditions. Triangulating these ii sources of information results in estimates that start in the mid-xx millions and get up to 45 1000000.

Two more contempo accounts give what are widely regarded every bit the most credible numbers. 1, in 2008, is by the Chinese announcer Yang Jisheng, who estimates that 35 million died. Hong Kong University's Frank Dikötter has a college but equally plausible estimate of 45 million. Also adjusting the numbers upward, Dikötter and others have made another of import indicate: many deaths were fierce. Communist Party officials shell to decease anyone suspected of hoarding grain, or people who tried to escape the death farms past traveling to cities.

Regardless of how one views these revisions, the Bang-up Leap Famine was by far the largest dearth in history. It was also man-made—and not because of war or disease, but past regime policies that were flawed and recognized every bit such at the time by reasonable people in the Chinese government.

Hu Jie: Permit at that place exist light #12, 2014

Tin all this be blamed on Mao? Traditionally, Mao apologists arraign any deaths that did occur on natural disasters. Even today, this era is known in Prc every bit the period of "three years of natural disasters" or the "three years of difficulty."

Nosotros can discard natural causes; yes, there were some problems with drought and flooding, but Cathay is a huge country regularly beset by droughts and floods. Chinese governments through the centuries have been adept at famine relief; a normal government, peculiarly a modernistic bureaucratic land with a vast army and unified political party at its disposal, should have been able to handle the floods and droughts that farmers encountered at the stop of the 1950s.

What of the explanation that Mao meant well just that his policies were misguided, or carried out also zealously by subordinates? Just Mao knew early enough that his policies were resulting in famine. He could have changed form, merely he stubbornly stuck to his guns in order to retain ability. In addition, his purging of senior leaders set the tone at the grass-roots level; if he had pursued a less radical policy and listened to advice, and encouraged his underlings to do so as well, their actions would surely have been unlike.

Simply Mao's policies were responsible for other deaths on top of those acquired by the famine. The Cultural Revolution—the ten-year period (1966–1976) of government-instigated chaos and violence against imagined enemies—resulted in probably ii to 3 one thousand thousand deaths, co-ordinate to historians such as Song Yongyi of California Land Academy Los Angeles, who has compiled all-encompassing databases on these sensitive periods of history. I called to ask for his estimates, and he said he would add another 1 to 2 million for other campaigns, such every bit land-reform and "anti-rightist" movements in the 1950s. The University of Freiburg's Daniel Leese gave me similar figures. He estimates 32 1000000 in the Smashing Leap Forward, 1.1 to i.half-dozen million for the Cultural Revolution, and another million for the other campaigns.

It is probably fair to say, then, that Mao was responsible for about 1.5 million deaths during the Cultural Revolution, another million for the other campaigns, and between 35 million and 45 meg for the Cracking Spring Dearth. Taking a middle number for the famine, 40 million, that's almost 42.5 million deaths.

At this point, I must digress briefly to deal with two specters that diligent researchers will observe on the Internet and even on the shelves of otherwise reputable bookstores. One is the political scientist Rudolph Rummel (1932–2014), a not-China specialist who made wildly college estimates than any other historian—that Mao was responsible for 77 one thousand thousand deaths. His work is disregarded as polemical, but has a foreign life online, where it is cited regularly by anyone who wants to score a quick victory for Mao.

Every bit scorned but extremely influential is the British-based writer Jung Chang. After writing a bestselling memoir nearly her family unit (the most popular in what now seems similar an endless succession of imitators), she moved on to write, along with her married man, Jon Halliday, popular history, including a biography of Mao every bit monster.

Few historians take their work seriously, and several of the most influential figures in the field—including Andrew J. Nathan, Timothy Cheek, Jonathan Spence, Geremie Barmé, Gao Mobo, and David S.Thousand. Goodman—published a book to rebut it. No thing: a dozen years after publication, Chang's piece of work is still on bookshelves around the Western world, while the Amazon blurb misleadingly calls it "the most authoritative life of the Chinese leader e'er written." According to Chang, Mao was responsible for 70 million deaths in peacetime—"more than than any other twentieth-century leader."

The "peacetime" adjective is significant because information technology gets Hitler out of the picture show. But is starting a war of aggression less of a crime than launching economical policies that crusade a famine?

How, finally, does Mao'due south record compare to those of Hitler or Stalin? Snyder estimates that Hitler was responsible for between xi million and 12 million noncombatant deaths, while Stalin was responsible for at least 6 million, and equally many equally ix million if "foreseeable" deaths caused by deportation, starvation, and incarceration in concentration camps are included.

But the Hitler and Stalin numbers invite questions that Mao'south college ones practice not. Should we let Hitler, specially, off the hook for combatant deaths in Earth War Ii? It's probably fair to say that without Hitler, in that location wouldn't have been a European state of war.

If 1 includes the combatant deaths, and the deaths due to war-related famine and illness, the numbers shoot up astronomically. The Soviet Union suffered upward of 8 meg combatant deaths and many more due to dearth and affliction—perhaps virtually twenty one thousand thousand.

Ukrainians starving in the street during the Soviet famine of the early 1930s (Photo past: Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images)

Then once more, wasn't Stalin partly responsible for those deaths, because he purged his best generals and adopted reckless military machine policies? As for Hitler, should his deaths include the hundreds of thousands who died in the aeriform bombardments of Germans cities? After all, it was his conclusion to strip German cities of anti-aircraft batteries to replace lost arms following the debacle at Stalingrad.

And what of the millions of Germans in the East who died later being ethnically cleansed and driven by the Red Regular army from their homes? On whose ledger do they belong? These considerations add to Stalin's totals, but they still more increment Hitler'southward. Slowly, Hitler'due south numbers approach Mao'due south.

And there is the sensitive matter of percentages. Mao's numbers are high because of the dearth, without which he wouldn't be in the running for butcher of the century. But if Mao had been the leader of Thailand, he wouldn't exist in the running: it was because his policies played out in China, with the world'due south largest population, that they resulted in such high absolute numbers of deaths. Then is Mao simply a reflection of the fact that anything that happens in China becomes a superlative? And that, by definition, the world's Pol Pots tin never compete?

Relativizing can be perilous. Every bit Snyder writes, "the difference between null and one is an infinity" (thinking, mayhap, of the dictum often attributed to Stalin that "a single decease is a tragedy; a one thousand thousand deaths is a statistic"). Information technology is true that we can grasp when a loved 1 dies but have a harder time accepting when the difference is between a one thousand thousand and a million and one deaths. But the right respond, of course, is that even i extra death tilts the scales. Death is an absolute.

Nevertheless all these numbers are little more than well-informed guesstimates. There are no records that volition magically resolve the question of exactly how many died in the Mao era. We can just extrapolate based on flawed sources. If the per centum of deaths attributable to the famine is slightly changed, that'south the difference betwixt 30 and 45 million deaths. And so, in these sorts of discussions, the difference between one and two isn't infinity but a rounding error.

Mao didn't order people to their deaths in the same way that Hitler did, so it's fair to say that Mao'due south dearth deaths were not genocide—in contrast, arguably, to Stalin's Holodomor in the Ukraine, the terror-famine described by announcer and historian Anne Applebaum inRed Dearth (2017). Ane can argue that by endmost downwards give-and-take in 1959, Mao sealed the fate of tens of millions, but virtually every legal organization in the earth recognizes the divergence betwixt murder in the first degree and manslaughter or negligence. Shouldn't the same standards apply to dictators?

When Khrushchev took Stalin off his pedestal, the Soviet country withal had Lenin equally its idealized founding father. That allowed Khrushchev to purge the dictator without delegitimizing the Soviet country. By contrast, Mao himself and his successors take always realized that he was both Cathay's Lenin and its Stalin.

Thus, later on Mao died, the Communist Party settled on a formula of declaring that Mao had fabricated mistakes—about xxx percent of what he did was alleged incorrect and 70 percent was right. That'due south essentially the formula used today. Mao'southward mistakes were set down, and commissions sent out to explore the worst of his crimes, simply his picture remains on Tiananmen Foursquare.

Xi Jinping has held fast to this view of Mao in recent years. In Xi'due south style of looking at China, the country had roughly thirty years of Maoism and thirty years of Deng Xiaoping's economic liberalization and rapid growth. Xi has warned that neither era tin negate the other; they are inseparable.

A Bejing street vendor selling souvenirs of China's present leader, Xi Jinping, and past leaders, including Chairman Mao Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty Images

How to deal with Mao? Many Chinese, especially those who lived through his rule, do and so past publishing underground journals or documentary films. Perhaps typically for a modern consumer society, though, Mao and his retentiveness accept also been turned into kitschy products. The first commune—the "Sputnik" district that launched the Great Leap Forward—is at present a retreat for city folk who want to experience the joys of rural life. Ane in x villagers there died of famine, and people were dragged off and flayed for trying to hide grain from government officials. Today, urbanites go there to decompress from the stresses of modern life.

Foreigners aren't exempt from this sort of historical amnesia, either. One of Beijing'due south most popular breweries is the "Great Leap" brewery, which features a Mao-era symbol of a fist clenching a beer stein, instead of the clods of grass and earth that farmers tried to eat during the famine. Maybe because of the revolting idea of a brew pub being named later a famine, the company began in 2015 to explicate on its website that the name came not from Maoist history but an obscure Vocal dynasty vocal. Only when you're young and fat, goes the verse, does 1 dare take chances a great leap.

Did Hitler Register All The Guns In His Country,

Source: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2018/02/08/who-killed-more-hitler-stalin-or-mao/

Posted by: mchenryanceirs.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Did Hitler Register All The Guns In His Country"

Post a Comment